I have a couple pro-writer friends who routinely watch shows like “American Idol” and “The Voice.” One’s suggested that I watch them, too, not necessarily for the entertainment value but because of what the shows are saying about risk and perseverance hold equally well across the various entertainment genres. The take-home for a singer might be very much the same as a take-home for a writer in terms of what you have to be willing to do to succeed.

Now, me? Gag me with a fork. I just can’t watch them, and because I’m not all that interested in singers per se (I know: sacrilege), forcing myself to sit there and try to glean something valuable is a waste of my time–and I don’t have a lot of that to waste, in any event. But I am interested in film, and so I pay attention when articles about actors or interesting celeb bios of any ilk (like the very fine book on Agassi (ghost/co-written by J. R. Moehringer whose The Tender Bar has to be one of the best memoirs I’ve ever read, or Rob Lowe’s terrific autobiography, Stories I Only Tell My Friends) hit. Those narratives frequently revolve around the same issues that “Idol” and “Voice” do: dedictation, perseverance. Failure, and more failure. And risk.

Today, I came across an article on Matthew McConaughey in the New York Times that’s worth a read if only because it brought home something I’ve noticed with Hollywood. Now, bear in mind that I’m writing this on Saturday night; I have no idea if McConaughey will win an Oscar or not–and in so many ways, that’s immaterial; I doubt I’ll be watching the Oscars because I actually don’t care who wins. But what leapt out at me was this:

“When he started making choices that were less based on his looks and had artistic integrity, a lot of young actors became very impressed,” said Laura Gardner, an actress and instructor at the Howard Fine Acting Studio here. “McConaughey has demonstrated a commitment to his art, to finding that truth in his characters.” She noted he lost 43 pounds for “Dallas Buyers Club.”

Really? Were people impressed because McConaughey ditched steady paychecks on the basis of a certain image? Did McConaughey really find “truth” in his portrayal of Ron Woodruff because he lost weight?

Get real. What matters here is perception and image and the perception of risk (real or otherwise). Look at what Gardner focused on: a perceived commitment to art based on the fact that the actor lost 43 pounds.

Think about that. Because this is nothing new. Going to this kind of extreme–losing weight, gaining weight, extreme physical makeovers–this always seems to impress people. (In fact, CNN’s got a whole spread on the phenom.) I’m thinking of similar comments about Robert DeNiro, who gained then lost then gained again to play Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull;

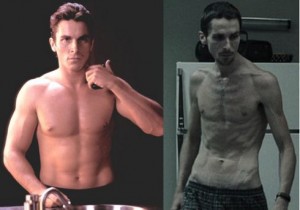

Christian Bale, who became scarily emaciated in both The Machinist

and Rescue Dawn

(I remember watching the former and being relieved near the end of the movie when we get to see Bale, in flashback and with forty more pounds).

Charlize Theron, surely one of the most beautiful women I’ve ever seen, who deliberately uglied herself up to play a more serious role in Monster and won herself an Oscar in the process:

Nicole Kidman doing the same–sort of–by outfitting herself with a big schnoz in The Hours . . .

and the list goes on.

Whether DBC is a good film or not (personally, I think it’s only an okay film)–whether McConaughey gets his Oscar or not–it doesn’t matter. What matter is this: in Hollywood at least, risk is often rewarded.

Now, this isn’t always the case; I can think of several movies (two with Michael Fassbinder) that were very risky (and one was, at the very least, risqué) that seemed to do little to catapult Fassbinder, a very fine actor, into a marquee name. But actors willing to do something very radical and wholly unexpected–something that might change their image–get attention, and as we saw last week when I talked about James Franco and Taylor Swift, attention is power. Right now, McConaughey is riding a very nice (and well-deserved) wave, and as the article suggests, it’s a highly scripted, deliberately choreographed one. Having seen a few of the actor’s earlier films–and, wow, was I underwhelmed–I remember thinking that the guy might not be a joke after all when he starred in The Lincoln Lawyer.

I loved him in the small role he had in Magic Mike (IMHO, he was the best thing about the whole bloody film).

The kinds of films he’s in now–Mud, The Paperboy, DBC–not to mention the absolutely terrific show he shares with Woody Harrelson, True Detective (my God, watch this one, people; the writing is so bloody good)

–those, I tend to notice. Not one’s a chick flick; the guy’s done a radical makeover, both as an actor and in his image.

What’s this have to do with writers? It’s actually simple, and it’s all about risk. Now, it’s true that writers have personae just like actors do. Some are more scripted than others; I know several writers who are very careful in how they present themselves to fans versus how they are with friends. I know more than a few who deliberately cultivate a certain style of dress, a way of speaking . . . and all that’s fine. A writer is creating a brand just like any other entertainer but, unlike an actor, a writer has the option of creating more than one. I’m thinking pen names here, of course (and even the canny outing of a pen name as an event that generates sales), but a pen name’s not absolutely necessary to create the sensation/illusion of risk. Sometimes simply changing genre will do it. I’m thinking here of John Grisham turning from legal-thrillers to what he perceived as more serious literary fiction (Bleachers; A Painted House) and children’s fiction (the Theodore Boone series). And, of course, James Patterson’s the master here, a guy who’s got a cottage industry going in pretty much any genre.

What those guys have done is taken a risk. They’ve stepped away from wash-rinse-repeat . . . and how many times have you wished your favorite author would do that? Just the other day, I was struggling to get through a book by an author I’ve enjoyed in the past. This is a book that people are waxing rhapsodically about, too, and so I’m thinking, Well, it’s me, I’m just not seeing what’s so wonderful. Actually, what I was seeing were shades of the author’s other novels: situations I recognized from different scenarios and yet which seemed to be heading toward the same, very predictable conclusion. I remember thinking . . . yeah, that cafeteria scene’s out of XYZ; this guy’s a dead ringer for Larry-Moe-Curly. You understand what I’m saying. Every writer repeats herself; you can’t help it, and it’s really okay . . . unless your scenarios become boring because you’re not taking any risks or stepping away from the formulaic.

The same pro-writer who told me to watch “The Voice” also taught me something very important: try something new with every book. In other words, stretch yourself and take some risks. Do the metaphorical equivalent of losing 40 lbs. and see what happens. For the record, I try to do that with every book. But I remember one in particular where my agent wasn’t sure it really was a young adult book. But she marketed it as one anyway–and it found its editor and audience. Just going to show that risk pays off if the product is also good because, clearly, taking a risk just for the sake of taking a risk does you no good at all if the product’s crap. (Like if you decide to run butt-naked through Central Park, at least be in shape and look good naked. If you don’t . . . you might want to reconsider.)

If you take a risk and come out with a crap-product . . . yeah, you might get some initial buzz for being “daring,” but that fades fast. No, what keeps you fresh as a writer–what might actually help you reinvent yourself–is if you’re willing (and able) to take risks. So, I’d suggest that whenever you sit down to write that next book, ask yourself these questions:

1) As a writer, are you able to leave behind the tropes with which you’re comfortable?

2) Can you see yourself switching genres?

3) Have you ever tried writing in a genre you’ve never attempted?

4) Do you try something new with every book?

5) Are you willing to write a book of the heart? Do you always try to write a book of the heart? That is, are you writing a book you really believe in? Or are you writing a me-too, something you think fits in with a trend?

6) (and the factor I think is most important) Are you willing to risk failure?

You have to dare to fail because failure is relative. You might have written a terrific book . . . but it might also be one that hasn’t yet found its audience, or is so diffferent that no one knows what to say about it (or just flat-out doesn’t understand). You might also have a turkey, too, and you have to be willing to acknowledge that. (I remember reading Stephen King’s preface to Under the Dome where he talked about having attempted the story a decade before only to slink off with his tail between his legs becaue he realized that he didn’t yet have the skill to putt it off . . . but at least he tried. He dared to take the risk, and eventually, it paid off.)

Same thing for the actors I’ve mentioned: they’ve all known failure. In fact, their failures–usually resulting in some huge crisis–forced their hand and galvanized them into doing something radical. (And I use “failure” loosely because failure is relative: if you’re still being offered and turning down potentially lucrative roles, like McConaughey, it’s hard to see that as failure. What that actor did was turn his brand name on its head, and reinvent himself as a “serious” actor.)

It is the same for us writers, and James T. delivers a great take-home we can all take to heart:

Isn’t that what fiction’s all about: daring readers to be people they’re not, living adventures they’ve never dreamt of but which you, the writer, have the courage to imagine?

So, for your next book? Jettison the old familiar tropes; jettison a genre, if you can and are willing to. Dare yourself to try something different. Stretch yourself; make yourself work just a little bit harder. Dare to imagine failure–but dare to imagine what might happen if you succeed.

Because risk is our business, too.