A couple years ago, some writer-friends and I were having this discussion about Obama and that brouhaha about Reverend Jeremiah Wright’s remarks about Jews and the like with another, much more seasoned pro writer-friend. I don’t even remember what the specific comments were, but I do recall my pro-friend turning to me and saying something like, “Listen, white girl, you just don’t know.” Now, I didn’t take offense or anything because my friend’s comment wasn’t meant as a slap. My friend was making a point that I, as a white girl (even a Jewish white girl, at whom some of these remarks were broadly directed), couldn’t really grasp the cultural milieu in which the comments were made.

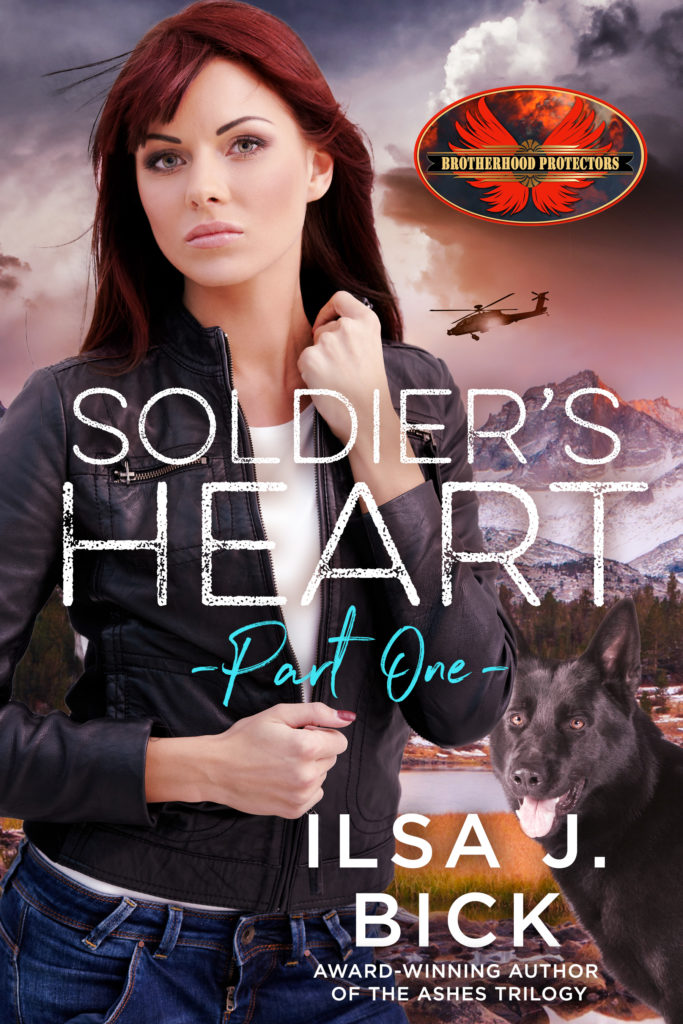

I believe my friend–to a point. It’s true that this friend is much more knowledgeable about black history; in fact, this friend wrote a very fine mystery series that featured a black protagonist. While the specifics of the series aren’t important, this is: at the time these books were out and about in the world, my friend wasn’t touring or publicizing them much for a very simply reason.

My friend is white. And of the opposite sex from the protag.

Talk about irony and (a bit of) reverse discrimination.

Why am I not more specific here? Honestly, I’m not trying to be a tease, but my point isn’t to out my friend. But I was reminded of this incident after reading the New York Times piece earlier this week all about young Latino readers and educators’ fears that these younger kids might not be as drawn into reading because there’s a dearth of Latino protagonists for them to identify with. Read the comments, and you’ll find both an even split and a wide array of responses. Some people think this is a big deal; others don’t.

Now I’ll be really honest here: by and large, my feeling is that this is another of those New York Times hand-wringing non-issues. You could say that I think it’s not, because as a white girl, I was in the majority back in the day and so always felt that I was being represented in one way or another in whatever I read–but you would be wrong. There really weren’t that many female protagonists out there for me to identify with. In fact, in a large proportion of both classical and contemporary lit, the protags were/are white males–and I can guarantee you that the overwhelming majority weren’t Jewish.

You want to read about diversity? Pick up any good sf with alien species as the primary protags–I remember one book that featured these funky insect-like creatures–and then tell me that I couldn’t possibly have enjoyed that because, oh, the protagonists don’t look like me. Back when I was a kid, there wasn’t anyone out there in either literature or film for me to take as a role model–and so what? I’ve never looked to books for role models, nor do I, as a writer, think about providing a role model for my readers. That’s way too preachy for me. Conversely, I don’t remember a single book that was just so influential I carried it around like a talisman or modeled my life after it. I wanted role models? They were called parents and teachers and other significant adults. ((I mean, my God, my mom was working outside the house, doing science stuff and going for a PhD in an era when women just didn’t do that. And who were her role models? Her father was a sponge diver and then worked in a rubber factory; her mother was a housewife. Neither went to college; I doubt my grandmother made it out of high school; they lived in a crummy section of Akron. But they all worked hard.) Similarly, none of my role models lived in books.

I’ll be honest (again): whenever I was handed the rare book with a Jewish protag (always male, as far as I can recall), I remember cringing. Reading stories about people I knew–folks I saw every bloody day–didn’t interest me in the slightest. Revisiting certain events in my cultural past–say, the Holocaust–was and remains a busman’s holiday. Then as now, I look to books to tell me a good story.

I may be really off-base here; maybe I just don’t get it. But when I’m immersed in a story, I couldn’t care less what the characters look like, or about ethnicity. (Oh all right, yes: if this is a romance that keeps mentioning that the girl is a size 2 and wears strappy sandals without breaking an ankle . . . yeah, okay, I may not want to step on the scale for a couple days, but I don’t stop reading on that basis.) When the story revolves around the character’s difference–Invisible Man and Native Son spring to mind–then, yes, of course this becomes an issue, because the difference is the story. But that difference doesn’t keep me from being able to either get into the story or feel along/identify with the characters either.

The magical thing about becoming lost in a book is that you also lose sight of who you are along the way. It’s really quite an interesting phenomenon, if you stop to think about it. You can both read yourself into a character and stand alongside at the same time. You get wrapped up in the adventure at the same moment that you may be thinking, Oh no, don’t do it! You can get mad at a character for being so stupid and still get a vicarious thrill with that first kiss. All of that speaks to the skill of the story-teller and–to my mind–has virtually nothing to do with what the characters look like, or whether they’re like me. (I mean, guys, think about it: are we really saying that kids can’t possibly identify with Wilbur because he’s a pig, and they’re not? That I can’t read about or enjoy or even identify with characters like Fiver and Bigwig in Watership Down . . . because I’m not a male rabbit? Get real.) Picking up a book is a way to get away from me now, just as it was a means to take me on an adventure and out of myself back then. The business of a book is not to instruct.

Which brings me back to my very talented pro-friend, who could fashion a thoroughly wonderful series about a character of a different gender, culture, and ethnicity, not because my friend was the same but because that writer was (and is) empathetic, passionate . . . and a damned good writer.

Now that’s what I call a role model.