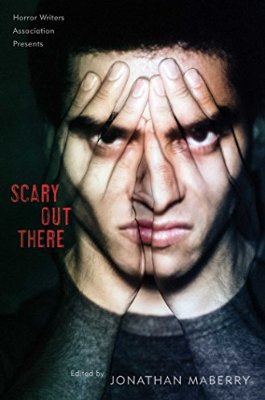

But it occurred to me that what we’re really interested in when it comes to horror–or rather, the emotion with which horror shares so many qualities–is the feeling of awe.

Think about it a second. Some of the most frightening visions in all religions begin with fear and shade to horror before giving way to awe (or both at the same time). People crave the mystical, the psychedelic, because what is so frightening is so awesome. The face of God is awesome because you have to cover your face to protect yourself against the majestic horror of it all. I’m no Bush-apologist, but he had it right when he talked about destruction evoking shock and awe: things so horrible you can’t bear to look away–and leave you wanting even more, hungry to re-experience this most powerful and visceral of emotions.

I’m particularly mindful of this right now in the wake of the Colorado shootings. Whenever something like this happens, eventually someone will ask me what I think, my theories, why this kind of thing happens. Being a shrink, you get used to the questions, and I guess people want to feel reassured that someone understands what the heck’s going on.(Just because I can put a label to something, though, don’t mean I understand. It means I can fit behaviors into a syndrome. I have ideas about why. But understanding is a truly different animal.) So no surprise that I’ve been asked a couple of times in the last day or so about the Colorado shootings. Now, I claim no special knowledge; I’ve not been following the news that closely. People will advance all kinds of theories, some of them sound and others pablum–but people are intensely interested. What I found fascinating was one guy I know who decided that the shooter must be an extreme sociopath of some flavor: someone so monstrous he just couldn’t relate at all. When I suggested that, in fact, the guy might have been mightily depressed–and depressed men and boy are frequently preoccupied with and act on very, very violent fantasies–my friend was a little . . . perturbed. In fact, he said, “Well, I guess that explains what was going on when I was a kid.”

Which makes you wonder.

For some people, believing the horrific to be alien is a comforting fiction. It feels better to imagine monsters as being incomprehensible, something you’ve got about as much in common with as a paramecium. Yet that doesn’t mean we don’t find the horrible and horrific–the monstrous–completely enthralling, or that monsters don’t have a home in your mind. I’m only being a little facetious when I say that everyone loves a good (fictional) psychopath just as people enjoy a good scare (or a great cry). (Meeting one in the flesh . . . well, not so much.) It’s why people flock to things like Batman movies and Hannibal Lector’s entered the popular lexicon; why folks ride killer roller coasters, read horror, or are mesmerized by terrible crimes. Keep in mind that the words “awful” and “awesome” are both derived from “awe,” from the Old English “ege,” meaning fear and dread. The Word Detective has a lovely write-up on this, by the way. To say that people want to reassured that the monsters will stay put is only stating the obvious.

While I’d like to think differently, I probably find the monsters–my monsters and their potential–just as fascinating. Not that I’m suggesting I’m so very special; no, what I’m saying is that, as a shrink who’s used to navel-gazing and really getting into the muck and slime–and as a writer who wants to put words to emotions so horribly awesome you don’t want them loose in the light of day–letting the monsters out to play is crucial. Being as brutally honest about the horror of which I am surely capable is vital to making a story–my stories–credible just as it is imperative for me to feel as if I’ve got a handle on them. I can let them out for a little while, but then I know how to put them back. (This is a problem actors have, by the way; more than one’s mentioned that when you play a thoroughly despicable and evil person seven days a week and twice on Saturdays . . . it takes a toll. Truman Capote discovered this to his ruin. On a more shrinkly note, Robert Keppel, who hunted Ted Bundy and the Green River Killer, has written very compellingly about the emotional toll, and a very fine film made about Keppel and Bundy, The Riverman, explicitly deals with this.)

In a way, I am no different than a kid who enjoys a good shoot-’em-up computer game, one where you blast the monsters to bits. It’s all about mastery, enjoying horror for the awe it engenders, putting it back in its place when you’re done.

This is not to trivialize tragedy. There are plenty of examples of novels delayed because they’re too close to reality (think King’s Rage). Our gun laws are insane, and I actually like guns. But I do think it’s worthwhile to take a step back and think about what it is about violence on the screen or in a book that we crave–and why it’s so awe-filled when the monsters come out to play.

Is there anything, psychologically speaking, in the idea that children love monsters that are significantly different from them (Godzilla, say), and that as we mature, we understand the world better and our monsters mature with us, becoming more and more like us?

BTW, I was on that panel with you. It was awesome, wasn’t it? 🙂

Hey, Alex: Yes, there is, actually, but only a tad. Kids’ fascination with monsters reflect not only the need to control themselves but also their attempts to deal with a scary world (think your nice dad and then consider the Hulk), and then the ability to “see” them as more normative (not deformed, for example) improves with age (although, not that much). Again, though, I think that the idea of monsters becoming more “like” us is only a fiction. We like to believe and need to maintain that the monsters are NOTHING like us; they’re always unfathomable or incredibly and evilly intelligent, etc. The entire mystery genre is built upon the exceptional detective bringing the monsters down a notch or two, to prove that we’re still their masters (think Moriarty and Holmes). I don’t think it’s any coincidence that Poe straddled the divide.

And it was an awe-some panel 😉