As many of you know by now, two prominent photojournalists–Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros –were killed in Libya this past week. You’ve probably seen their pictures without knowing who they were; if you’ve watched Restrepo–and if you still haven’t, shame on you; what are you waiting for: an engraved invitation?–then you’ve got a fine sense of the risks war correspondents run. Why they do it is, I suspect, as individual and varied as the journalists themselves, although Joao Silva, a photojournalist for The New York Times who lost both legs last October while covering the war in Afghanistan, had this to say to Fresh Air’s Terry Gross:

Mr. SILVA: You know, I have this fascination and, you know, to be on the cutting edge of history, witness history firsthand, you know, making documentation of it and somehow be productive in society by doing so. I’ve always wanted to show those that are fortunate enough not to live in a warzone the realities or, you know, certain realities of warzones, which is ultimately the point, you know. We go out and we expose ourselves, you know, believing that somehow, we have an impact on society. For the most part, we don’t.

You know, people are more interested in getting their iPad 2 and all that kind of crap than what goes on in Afghanistan and Iraq. But, you know, I’ve always believed that if you actually, you know, managed to change one single person’s mind, or at least inform one single person, then you’ve accomplished something. So, yeah, you know, we’re not changing the world out there with pictures, but we’re certainly trying to inform the world. So, yeah. That’s basically it.

If you’ve been awake these past few years, you know Silva’s work:

And if South Africa blew you by, then let Marinovich’s Pulitzer prize-winner of a young boy being macheted as he is burning to death refresh your memory:

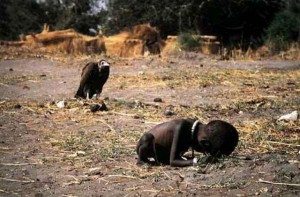

Do listen to the program in its entirety, too; Gross also talks to Marinovitch, who co-authored The Bang Bang Club with Silva. The book documents their experiences covering the fall of Apartheid from Mandela’s release in 1990 to free elections in 1994. Of the four photojournalists who formed the Bang Bang Club, two are dead. Ken Oosterbroeck was killed in 1994 in the same incident in which Marinovich was badly injured. Kevin Carter, who took this haunting Pulitzer-winning photograph of an emaciated Sudanese girl struggling to save herself as a vulture patiently waits, committed suicide:

The movie of that book was also released this week.

Regardless of a correspondent’s motives–and I suspect there’s more to it than simply or only bearing witness just as there are many reasons kids volunteer for the military–war correspondents must be, as a bunch, a very interesting group of people. Some, like Hemingway or–hang onto your hat–Al Gore, become famous for different reasons. What should surprise no one is that the same problems soldiers face–increased rates of substance abuse, depression and PTSD–also affect war correspondents as this nearly decade-old study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry concludes.

Kevin Carter said it much more baldly in his suicide note:

The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist . . . I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings and corpses and anger and pain . . . of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners . . .

I don’t pretend to understand the ethical divide journalists must struggle with; Sebastian Junger talks about this in War just as Marinovich and Silva do in their book. But one reviewer posed this fabulous question about The Bang Bang Club: Does a film with handsome actors and beautiful images of terrible events glamorize misery, or does it introduce a little-known calamity to a wider audience?

I don’t pretend to know the answer to that one either. I suspect there is no one “right” answer. In a way, you could ask the same question of another terrific film, Under Fire (Roger Spottiswoode; 1997), a portion of which is based on a real event: the 1979 shooting of ABC reporter Bill Stewart by a Somoza soldier. In that instance, public outrage was enough to force our government to come out openly against Somoza and, as they say, the rest is history. While the movie version of the incident isn’t exact–Stewart was forced to the ground and then shot–you get the gist.

I doubt the same will happen here, of course. The situations are different; Stewart was murdered with a bullet to the back of the head; Hetherington and Hondros were killed by shrapnel from rocket-propelled grenades. All were casualties; all were, because of their jobs, celebrities in a way. I think what saddens me is that what happened to Hetherington and Hondros was no different than what has happened–and continues to happen–to thousands of American soldiers who remain faceless except to their families and friends. They may make the evening newscast–a brief snapshot–or a mention in the local paper, but that is all because they’re not celebrities.

They’re only our soldiers.

I don’t know exactly what I’m groping toward here, but I think I’m bothered by how easily we seem to be going about our lives while remaining relatively ignorant–and apathetic–about what’s going on with the soldiers we would depend on to protect us if someone should, G-d forbid, attack the U.S. That is, the wars are over there and far away; ask the average Jane if she even knows what the two war ops are called, and chances are that she won’t. For all of you busily taking that quiz, they’re Operation New Dawn (Iraq) and Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan)–and don’t be surprised if you didn’t know. The Obama administration went for New Dawn in early 2010 and as this article makes clear, name changes are common.

Which is a little troubling, if you ask me. I can just hear the spin-docs now: Look, it’s all about packaging . . .

But, you know, a wormy rose by any other name will still stink, and no matter what the name, when there’s no personal investment or sense of shared mission, purpose or sacrifice, then it’s very easy to simply not care.

I have this bracelet I got a while back that I almost always wear. It’s stainless steel and so quite reflective, but here’s a decent picture of what it looks like:

Mine’s not quite the same. I opted for one that reads:

OND & OEF

UNTIL THEY ALL COME HOME

Because I was in the Air Force, I opted for that seal on the left and an American flag on the right.

Now, do I wear this because I’m a right-wingnut? No. Anyone who knows me understands that I’m a left-wingnut. I wear this bracelet for a couple of different reasons. One’s pretty straightforward; the bracelet is a symbol of my respect and support, and part of the money goes to charities for families of heroes and victims of terrorism. Two, the bracelet forces me, every now and again, to think about what more I should or could do.

But, thirdly, the bracelet makes other people curious. I opted for initials instead of having everything spelled out so that people would ask what OND and OEF mean, and I get those questions, maybe, twice a week. And that means I’ve forced two more people to slow down and think–about our soldiers, about where our fellow citizens are, about whose boots are on the ground. (By the way, if you don’t think we’ve got boots on the ground in Libya, guess again. Who, exactly, do you think is calling in those Predator drones?)

So, in a way, I wear the bracelet . . . for you. To prompt you to ask me the questions–so you slow down and remember them.

You should think about Hetherington and Hondros, but you should ask the questions and examine the emotions they and their fellow journalists elicit with their work. You should slow down.

You should think.

You should remember.