This past week, Kris Rusch began a series on her business blog about traditional publishers and “discoverability,” which is exactly what it sounds like: getting the word out about your book. Take the time to read this because she’s talking about stuff near and dear to our hearts as writers. (Some of the comments are just superb, too; in particular, check out John Brown’s discussion of marketing dollars and distribution models.)

All of us are invested in rising about the noise, and as Kris points out, traditional publishers have been all over this in various ways for years. What she also highlights is that the assumption that somehow a traditional publisher will do a big, involved promotional campaign for a book is dead wrong. The math is really simple: if your advance is low, the amount of bucks (and time) your publisher will spend on advertising your book will be negligible.

That’s because ad campaigns are expensive. Single page ads can be obscenely high-priced (Rusch has some good examples in her post). Heck, just about everything involved in marketing is pricey—and that includes the time a publisher devotes to your book. In other words, advertising your book isn’t only about getting an ad in a magazine or something; it also involves tying up people to make calls, do emails and social media, etc. Time truly is money here.

So unless you’re Stephen King, or you hire your own advertising firm (as James Patterson does), or you’re a newcomer w/ buzz and some super-duper advance, you can pretty sure that marketing for books by you, Mere Mortal, won’t be a full-court press of any sort, unless that’s all part of some marketing guarantee you set up in your contract. (And have you really paid attention to marketing campaigns in your contracts? Does your contract even have a section that deals with marketing? Almost all do, by the way, but they can be very vague.) Even things that might be promised—say, on the back of an ARC—don’t necessarily happen.

And speaking of ARCs—by the way, folks, those things are obscenely expensive to produce, which is why it’s disheartening to see people acting like jackals over roadkill at venues like BEA and no, you are not entitled to walk off with boxes and boxes of freebies—take a look at the back of an ARC sometime to see what I’m talking about. There’s almost always a little section devoted to the marketing campaign. What you find is a pretty good indicator of just how much time and money your publisher’s going to spend on your work. Although just because a campaign promises author appearances at conferences . . . that doesn’t mean they’ll necessarily happen. Just as Rusch’s calculus is based on advances (that is, no one is going to spend ridiculous amounts of ad dollars on a book with a $5,000 advance), I look at these tidbits as code for how well the publisher expects a book to do—and how much your book is really worth to them. (Same thing when a publisher announces a print run: if they go to that trouble and it’s a big run, that’s code for we expect this book to do well.)

So if the campaign is something like, well, there will be a pre-pub trade advert with a galley giveaway, or a publicity mailing, or “select print advertising based on review coverage” . . . think about it, guys: that’s pretty minimal. Heck, if you don’t get some decent reviews, your book can get forgotten pretty damn quick. (And the reverse is true: if you happen to get some great reviews, all of a sudden, your publisher might pony up some extra cash to get the word out.)

Thing is, no one’s really quite sure what works in terms of getting readers to pick up your book. There’s also no good way to get any solid data (or answers) about whether an approach worked or not. I’ve had that happen to me; there was a certain amount/level of advertising for a particular book. But then when it came around to another book, it became very clear to me that the advertising push was much less. When I asked why things that had been done before weren’t being done again, I got kind of vague answers, and most of them something along the lines of there being no evidence that a particular approach worked.

But my point would be . . . that’s unknowable. You have no evidence that the particular approach didn’t work. No one knows what might prompt someone to pick up a book. How can you measure that? You can’t. But I also understand the code here: we’re not putting as much money into advertising your book because we don’t think that will be money well spent. In other words, your book isn’t worth it.

Rusch is right when she says that ads are informational—marketing tools designed to let you know that the book’s out there—although I disagree with Rusch’s assertion that an ad is unlikely to convince a reader to pick up a book she otherwise wouldn’t. I say that because I’ve picked up books on the basis of ads (just as I’ve given books a try if there’s a blurb by a writer I know and like). Ads also cue me in terms of when a book’s come out (which is, after all, what ads are for). Yeah, yeah, I know about putting release dates on my calendar and setting up wishlists and all that . . . but if I don’t look at my calendar or get some sort of other clue that a book’s come out, I know I’ll flat-out forget. Those wishlists from Amazon? Pointless. They don’t send you an update saying, Hey, that book you were interested in is out. I’m telling you: something like that would be nice. People are busy; they need little memory jogs.

So how do you get someone to connect with your book? Tell me, and we’ll both know. I’ve done blog tours, blogs, giveaways, appearances, talks, book festivals, interviews. I have absolutely no idea if any of that really helped. None of it hurt, that’s for sure, but as with measuring the effectiveness of an ad campaign, there’s no way to quantify this just as there’s no justification in assuming that, say, guest posts are the way to go because–supposedly–blogs set tastes and trends. (I actually had a marketing person say that to me. I was too intimidated to say what I thought: Oh, really? And your data is . . . where? How do you know which blogs set tastes and trends? You are aware, of course, that the number of followers means nothing?) This is the same stuff I heard about why I just HAD to do book trailers, which were all the rage a while back; I’ve even had a company assure me that, you know, even Hollywood producers look at trailers. Again, uh . . . and you got numbers to back that up? Examples? This is like saying that every person who self-pubs will make gamillions and become Amanda Hocking or E.L. James. Yes, yes, there’s probably always the outlier, but I’m talking about us mere mortals. (And take some time to read what Hocking says not only about the actual stress of self-publishing and burn-out; how she’s driven nuts knowing that a lot of stuff has errors; etc., etc. Sobering reading. I’m not bashing self-pubbing. I’m only suggesting that it’s not the panacea a lot of people might imagine, and there is also this: if you are paying for someone to edit your work, where is that person’s incentive to tell you that your work isn’t all that good? Or could use massive revision? Think about it for a second. This came home to me in a very dramatic way just the other day when I had lunch with an artist-friend, who’s working on a commission he’s not wild about: which, in fact, he thinks isn’t his best work at all and is, frankly, kind of stupid. But he’s doing it because he needs to eat and he wants the job and the sale and, maybe, to garner some notice. So he’s just sucking it up and muscling through as the people who commissioned the work tell him to put more mountains here or lakes there. Could he tell them that would ruin the painting? Sure. Will he? He’s not stupid. Unless you’ve got an extraordinary relationship with the boss–which freelancers of any ilk frequently won’t have–you keep your mouth shut. If you, Mere Mortal writer, have employed a freelance editor . . . you seriously expect that person, who also needs to eat, to tell you that what you’ve written sucks?)

We all know that, mostly, getting books into people’s hands so they have a chance to see it, read it, flip around . . . that’s what’s important. And I’ll be right up front here, too: Amazon’s “look inside” isn’t any kind of substitute for a real book-book. Neither is Google Preview. They’re just not that helpful (to me). I have yet to buy a book on the basis of an Amazon excerpt or Google Preview. I like (and need) to flip around a book. I don’t like anyone telling me that I can only look at this one little piece because—IMHO—it’s easy to give people something whiz-bang for ten pages. But sustaining that is harder, and there’s no way that you, the reader, will be able to judge if the writing gets flatter, less interesting, etc. Conversely, some truly excellent books need time to get going . . . but with Amazon’s current model, you won’t know that either.

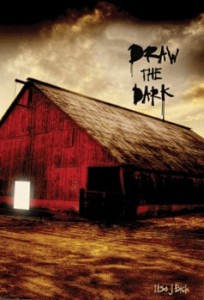

Anyway, as I gear up with a new series that I know is so vastly different from what I just finished and my standalones, I’ll be interested to hear what Rusch comes up with in the next few weeks in terms of better ways of getting a book those much-needed eyeballs. You should be paying attention, too.

As they say the writing is the easy part all things considered.

Yup. And even then…

This is what horrifies me. If I happen to score my publishing dreams I will then have to market and that gives me nightmares. I’m an introvert and it’s difficult for me to shill myself.

Yep. And it’s only going to get harder as more and more of the onus falls on us to make books go, or if you jump ship to go it alone.