In Stephen King’s Dreamcatcher, there’s a scene where all the wildlife is streaming through the woods, trying to escape from the aliens. A lot of stuff happens before and after, but that’s one scene I’ve always remembered, both from the book (whose first cover I do believe referenced that) and the movie.

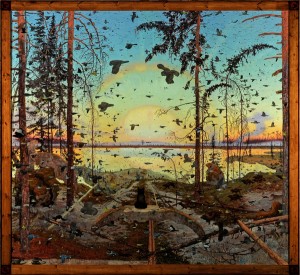

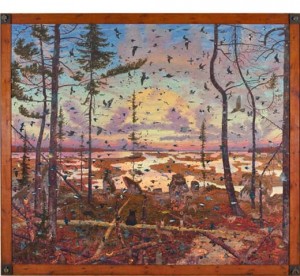

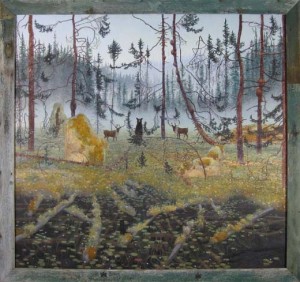

I thought of King’s book three years later–seven years ago now–when I had the great good fortune to wander into the Milwaukee Art Museum for an exhibition of a Wisconsin painter I’d never heard of. His name (then and now) is Tom Uttech, and the exhibition, Magnetic North, was a real eye-opener. Tom was deep into what people have called his “migration” paintings which, to hear him talk about them, is as good a word as any: short and somewhat descriptive. Tom’s migration paintings are like that: all kinds of animals fleeing from some unseen danger, some painted on these HUGE canvases. These paintings are stylized, brooding masterpieces, full of menace and frenzy. Those animals are running and flying away from something really bad–and the danger spills out of the paintings onto the frames which Tom makes by hand for each painting, incorporating elements that both further and complement the painting. Of course, not all his paintings are like this; there are just as many paintings that are quiet and contemplative. But I really responded to the menace in these. This artist is a genius.

Tom Uttech, Enassamishhinjijweian, 2009. Oil on linen, 103 x 112 in. © Tom Uttech; Alexandre Gallery, New York.

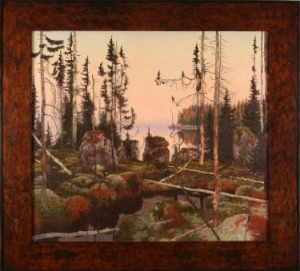

Tom Uttech, Enassamiian, 2009. Oil on linen, 33 x 36 3/8 in. © Tom Uttech

Tom Uttech, Detail from Nind Awatchige, 2003. Oil on linen, 112 X 122 in.; © Tom Uttech; New Orleans Museum of Art

Since I’ve been a Tom Uttech fan-girl for a while now, I was thrilled to attend a new exhibition of his work, Boreal Conversations, at the Tory Folliard Gallery here in Milwaukee. (Tory’s gallery and the Alexandre in New York are the only places where Tom’s work can be had.) Tom’s work has really evolved, and while he still had one big migration painting on display (going to the Chassen; lucky dogs)

Tom Uttech, Nin Mamakadendam, Oil on Linen, 91 x 103″ in. © Tom Uttech; Collection of the Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison

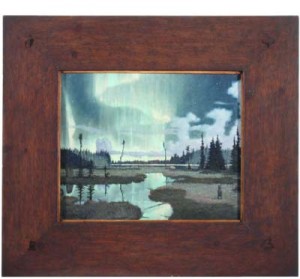

the majority of his work is much quieter now and more contemplative. Some pieces still have a lot of mystery to them, but these works invite you to immerse yourself in something mystical rather than wonder about what’s off the canvas. In fact, this painting

Tom Uttech; Makwa Pindig-Wabashkiki, Oil on Linen, 66 1/2 x 71 1/2″ in. © Tom Uttech

reminds me of this painting by LaPage:

Jules Bastien-Lepage, Joan of Arc, 1879; Oil on canvas; 100 x 110 in; New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Why? Beats the hell out of me. I’m sure it has something to do with the coloration . . . and a lot to do with mystery.

Tom gave a fabulous talk, and it was really interesting for me as a writer to hear that Tom feels the same way about his work as I do about mine: that, half the time, he’s making a real mess of things.

I actually felt relieved to hear how an artist I really admire sometimes HATES what he’s doing, only to find his way to doing something he’s ultimately proud of. Just about every writer I know–me, included–feels the same way right around the dreaded middle third of every book. I’m there right now with the ASHES sequel (and, as Tom pointed out, thank G-d for deadlines, imposed either by yourself or someone else; I put a deadline on everything I write or else I’d never stop tinkering). It was also fascinating to hear Tom talk about the importance of structure in trying to get across whatever story he’s painting; in a way, Tom’s focus on where to place a tree, how to direct the eye is the same as figuring out how to pace a book or move people around in a scene.

But what was really fascinating was to find out that Tom hides things in his paintings. Some things are there to be found–like the Ojibwe trickster Maymayguishi or various animals (there’s a very early triptych of his at hanging in the bar at Blackwolf Run here in Kohler, and the challenge is to find all the animals hidden in the landscape). But others are known only to Tom; he talked about how he included woolly mammoths and flocks of passenger pigeons in that painting he did for the Chassen . . . and then covered them over. He knows where they are, but we don’t. I think this has something to do with what Tom wants to inspire in anyone who views his work. He invites you to wonder about presence, whether that’s the presence of a wolf crossing the landscape at this very minute, or the bird that flew over that lake ten or a thousand years ago.

This fascination with mystery extends to the names he gives his paintings. They’re all Native American (largely Ojibwe) and while some reference real places on a map, none ARE real in that sense. But Tom is interested in origins, and the names he gives his paintings reflect his reverence for the original language as much as they do the land where man has no place. There are, in fact, no people in his paintings at all, although he will often use a bear as a human stand-in. Look for the teeny, weeny, eensy bear in this:

Tom Uttech, Nind Agotagos, 2010, Oil on Museum Board, 16 1/2 x 18 1/2″ in. © Tom Uttech

So if you’re in Milwaukee or New York in the coming months, give Tom a look-see. Keep an eye out for his shows–and, as friend of mine once said, prepare to get your mind blown.

What’ll make this girl happy? An Ilsa Bick book with a Tom Uttech cover. Right . . . and what illegal vegetable matter have you been smoking?

******

Apropos of absolutely nothing, here is a fabulously funny recut trailer for The Shining. Thanks to my daughter for shooting this my way:

Hmmm, I don’t see menace in _Enassamashhinjijweian_ for two reasons: the title is Ojibwe for “Hope of good things to come,” and the bear’s not running. He’s sitting there contemplatively watching. I love this painting. It captured my imagination when I first saw it at Crystal Bridges in Bentonville, Arkansas. But it fills me with hope and longing. And it reminds me of the North Woods, where I love to hike. And of the Anishinabe friends I have up there. It also reminds me of the accounts of many early visitors to North America who described a sky filled with birds during migration seasons. In Michigan, flocks of passenger pigeons used to block out the sun in the 19th century before they were hunted to extinction for squab. So the painting is perhaps both nostalgic, mourning a lost past, and hopeful that it may one day return. Stranger things have happened in Earth’s long history.

And this is why art is so much fun: because it’s all in the eye of the beholder 🙂